Operating with a Robot

“I was a wild kid,” José Oberholzer admits with a laugh. Even as a little boy, he once cut open a teddy bear, only to be disappointed that it was stuffed with straw. These days, he no longer operates on toys but on people – with interventions that help them build new lives. A professor at the UZH Faculty of Medicine, chief physician and chair of the Department of Visceral Surgery and Transplantation at University Hospital Zurich (USZ), Oberholzer and his team in Chicago were among the first in the world to perform robotic organ transplants 20 years ago.

Since then, he has performed over 500 such operations and trained numerous surgeons in the technique. He routinely transplants kidneys and pancreases and removes tumors from the liver and pancreas. Nowadays, he often assists in surgery to pass on his experience to the next generation.

Tight time frame

This week, he’s on liver duty. It’s quiet for now – no surgeries scheduled. We’re sitting in his office just after he’s returned from a research meeting. The topic was organ perfusion – preserving the viability of the transplant while it’s outside the body. This is particularly delicate with liver transplants. Unlike kidneys, which can be preserved for up to 36 hours, livers remain viable for only about 10 hours before irreversible damage occurs.

“Since there’s no backup therapy like dialysis for kidneys, a patient can die if the liver doesn’t function quickly,” Oberholzer explains. Using a new method developed by his team, they can now measure liver quality in real time, giving them greater confidence that the organ will continue to function after transplantation.

Researcher and surgeon

Sitting comfortably in his white coat, José Oberholzer speaks in a calm, warm voice. In the background, a simple bed stands discreetly behind his desk – a place to rest after long nights in the operating room. He studied medicine in Zurich and Fribourg, and after several years of surgical training and traveling, joined the University Hospitals of Geneva in 1996.

“Those years were of pivotal influence, shaping both my career and the broad surgical repertoire I have today,” he says in retrospect. In Geneva, he received solid academic training and was able to enter laboratory research, where he contributed to early studies on cell therapy for diabetes. And before long – despite his young age – he was head of the research group for islet cell transplantation.

The early surgical robots were like Fiat 500s. Today we’re working with Ferraris.

But the ambitious young Oberholzer didn’t want to stay in the lab, he wanted to be a surgeon, too. “I realized I needed a lot of surgical experience if I ever wanted to be one of the best.” He managed to convince his boss, Philipp Morel – who would rather have kept him in the lab – to let him operate as well. “I’m still very grateful to him,” Oberholzer says. “He’s like a father to me to this day.”

From Morocco to Urdorf

After six years in Geneva, Oberholzer was ready to venture abroad. He first took up a fellowship at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, before moving to the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System in Chicago, where he first became a professor of surgery, bioengineering and endocrinology and then, in 2007, chief physician and head of the transplant program.

“Originally, I only planned to stay three years before returning to Switzerland,” he sighs – and then chuckles. But three years turned into twenty. His wife, a neurobiologist – his high school sweetheart from their days at Limmattal Cantonal School – agreed to the move and initially chose to focus on raising their children. Gradually the family settled into life in the United States.

When asked how he would describe himself, Oberholzer grins: “I’m a ‘mixed breed’.” He was born in Morocco and lived in Tangier until starting school. His mother is Spanish – hence his first name – and his father a banker from Uznach. “He was an adventurer and liked traveling,” says Oberholzer. It was in Morocco that his father started a family. When young José was due to start kindergarten, the family moved to Urdorf, near Zurich. " I didn’t understand a single word at first,” he laughs. But he quickly adjusted and went on to enjoy a typical Swiss childhood.

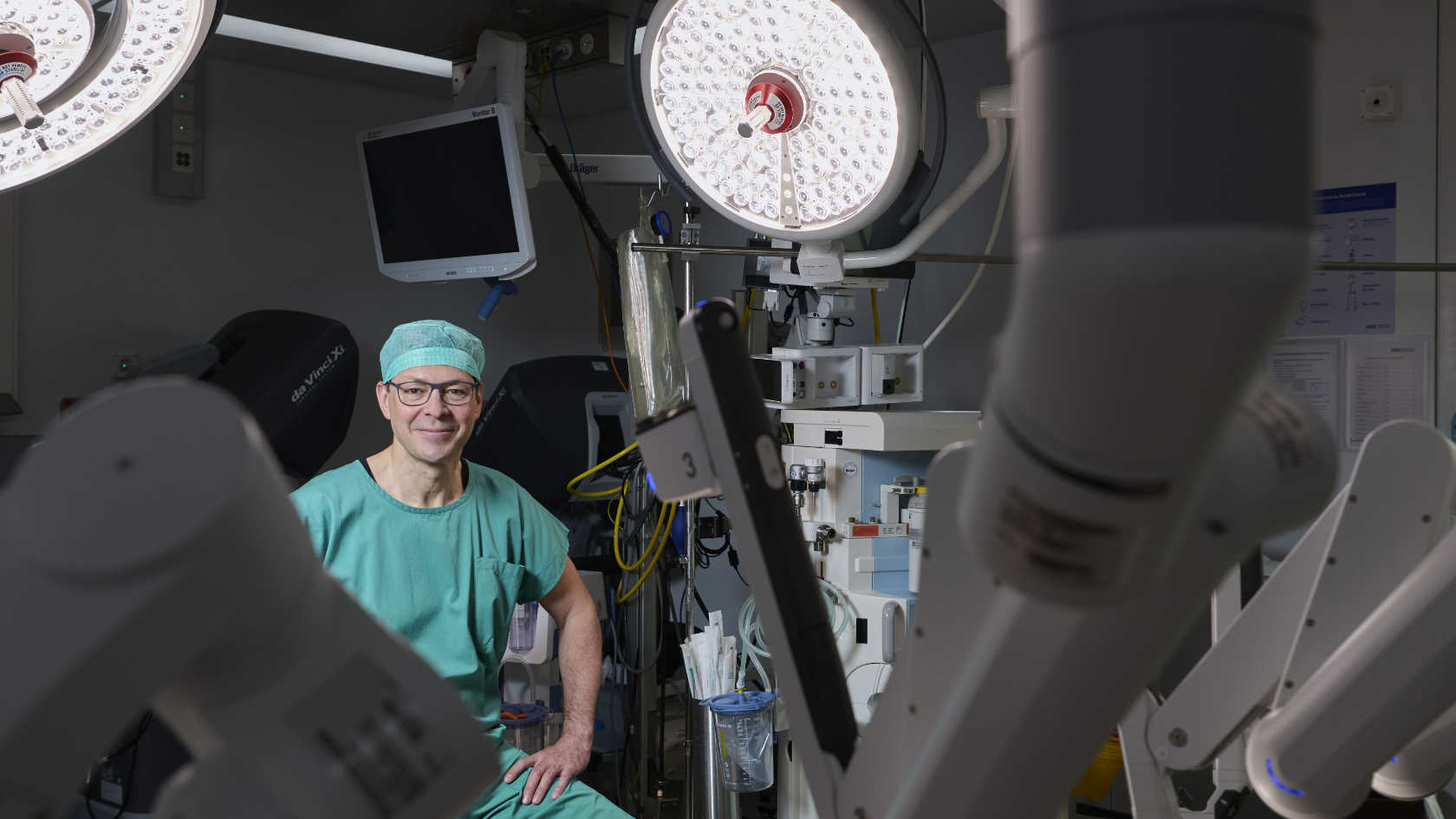

He pauses for a moment, then returns to his time in Illinois. “That was a lucky coincidence,” he says, shaking his head. The hospital was the first in the world to have a surgical robot. “That put me right at the forefront of robotic surgery.” In 2008, Chicago surgeons performed the world’s first robotic kidney transplant. Oberholzer recalls operating with the first-generation of Da Vinci, as the smart beast is called. “The early surgical robots were like Fiat 500s. Today, we’re working with Ferraris.”

Teamwork in the OR

Cut to Operating Room 2 at USZ, 8:00 a.m. The mood is calm and focused. On a raised unit in the center of the room lies the kidney donor, head and body draped in sterile covers, robotic arms in place overhead. José Oberholzer and senior attending physician Fabian Rössler are the surgeons performing the operation. Rössler was trained by Oberholzer in robotic surgery and the two work well as a team.

The procedure is a kidney extraction for transplant, a minimally invasive operation that requires only small incisions. As long, precision instruments enter the abdominal cavity through a small, protected opening, Oberholzer, who’s positioned at the patient’s side, watches the procedure on a screen.

Rössler is in charge of the robot. Seated at a console against the wall, he leans into a sort of viewing hood, inside which he sees a 3D image of the patient’s abdominal cavity. His practiced hands make small adjustments with the control levers. The two surgeons work with concentration, uttering only the odd word, and free the kidney. After around an hour and a half, Oberholzer says it’s time to notify the team upstairs that the recipient can now be taken to anesthesia. It will be another hour before the organ is actually removed. By then, the patient will be ready for the transplant in the operating room one floor up.

A grateful speaker

Back in Oberholzer’s office, the many green plants create a pleasant atmosphere. He shakes his head with a laugh, recalling a moment in Greater Washington when he stood at the podium as keynote speaker at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In the audience were representatives from both the NIH and the Food and Drug Administration FDA – the same institutions that had approved his team’s islet cell therapy for diabetes. “I suddenly got emotional and had to briefly pause my speech,” he recalls. He was seeing himself – once a small boy from Limmattal – now standing in front of all these brilliant people whose books he had studied during medical school. “In that moment, I realized how incredibly lucky I’d been in life.” It was a defining moment.

More and more often, he found himself thinking it might be time to return to Switzerland. “I had so many opportunities in the US, I was able to realize my potential and I was very grateful for that. But all the people and institutions that had encouraged, trained and supported me were in Switzerland,” he says. He wanted to give something back.

José Oberholzer spent two decades living in the United States, working, researching and teaching. His now-grown children – one an environmental scientist, the other a budding architect – are still there. From US culture, he’s brought back a belief in flat hierarchies, a culture of mentoring, and a sense of teamwork. He pauses again. He looks relaxed. But then it’s time to go – to the next appointment in his tightly packed schedule.